Defenders not only have to keep up with ever-evolving threats, but also with the Rosetta Stone of threat names spread across organizations. Microsoft with its types of weather, Mandiant (now Google Cloud) with its UNC/APT system, CrowdStrike with animals, Unit 42 with constellation names, and the ever-growing smattering of smaller firms with intelligence groups using their own or no naming convention at all. The fatigue this heaps on defenders has been harped on endlessly already, but I argue that keeping company reporting separate, along with the ease of maintaining the Rosetta Stone, outweighs all negatives.

The Visibility Problem

Visibility into the Operational Environment determines a threat research group’s capabilities.

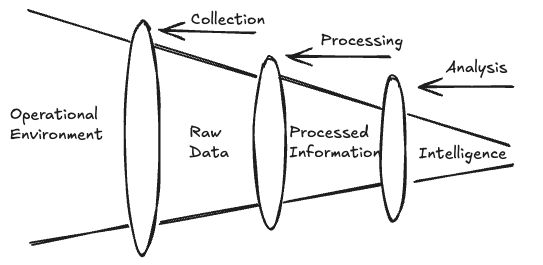

When we talk about the process of intelligence creation, we often reference the old but evergreen threat intelligence pipeline.

There is a lot that has been said about collection, processing, and analysis, but rarely do we talk about how visibility into the Operational Environment (OE) determines a threat research group’s capabilities.

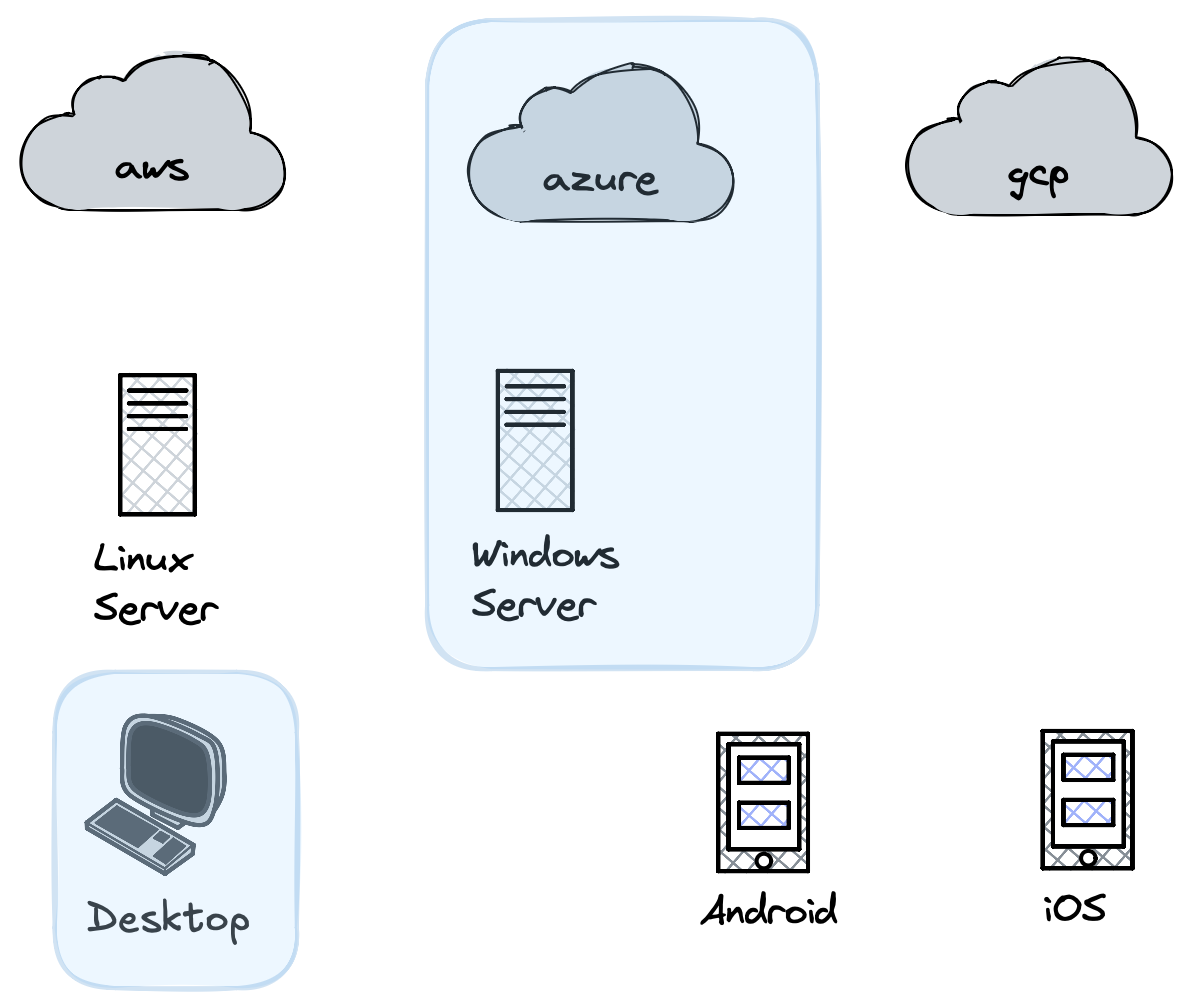

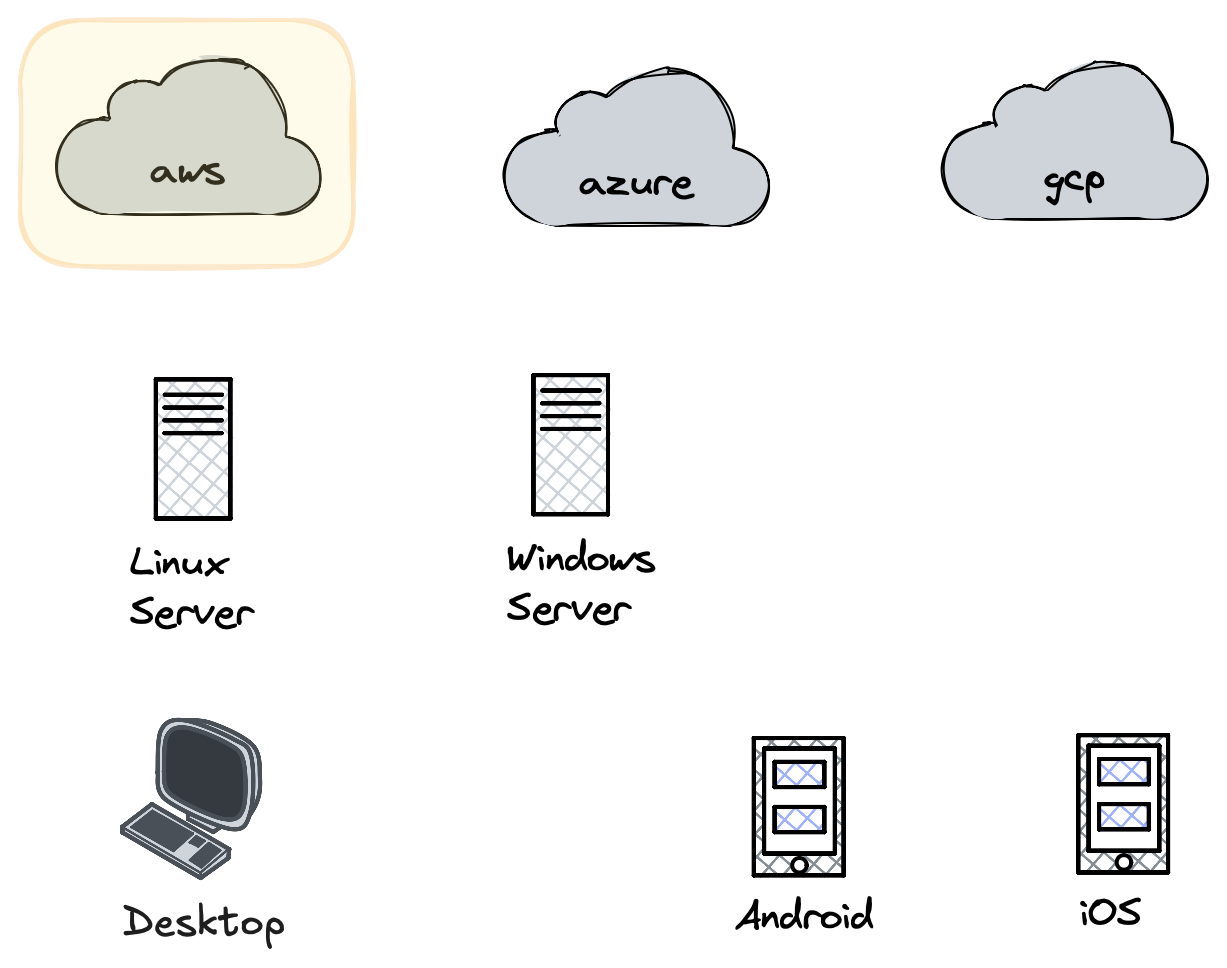

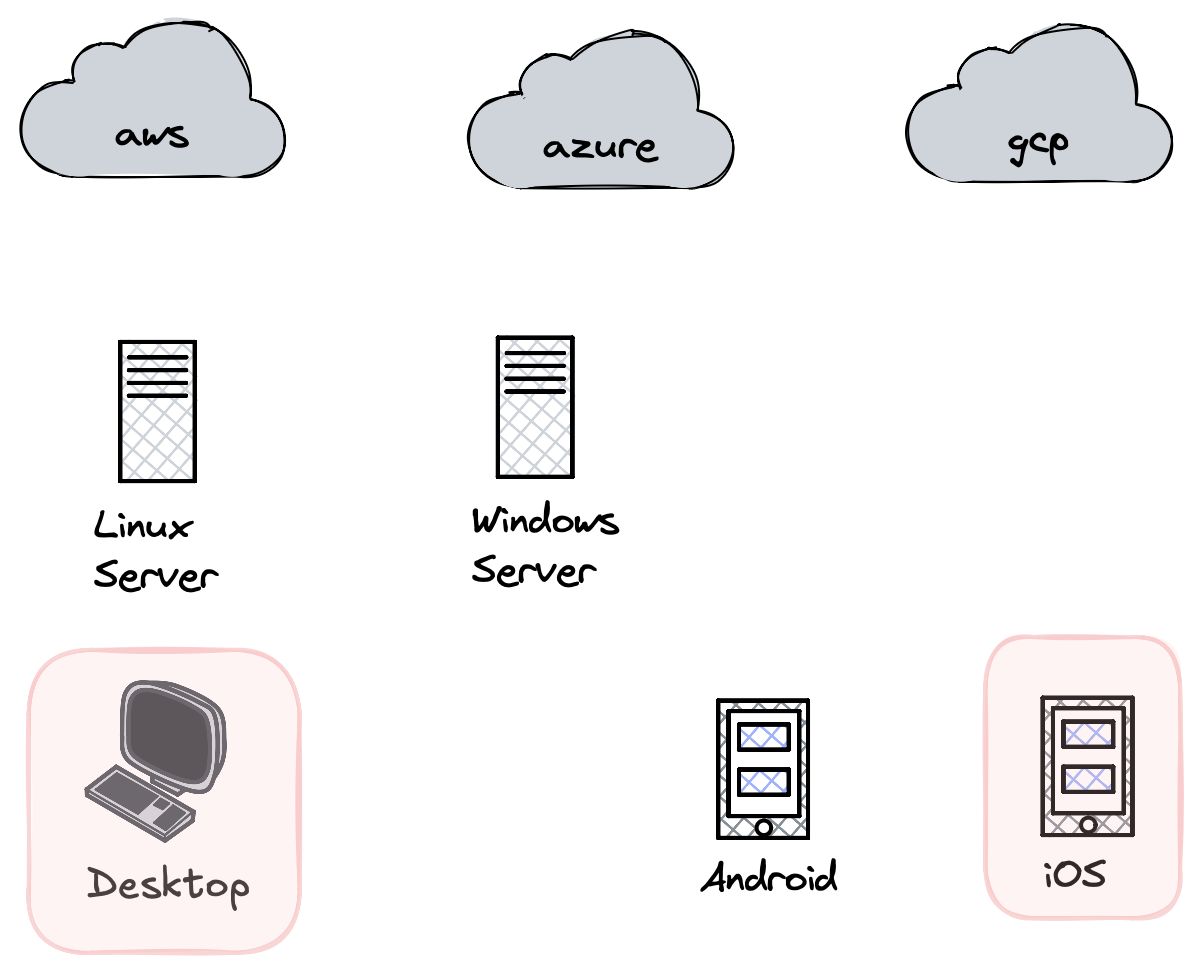

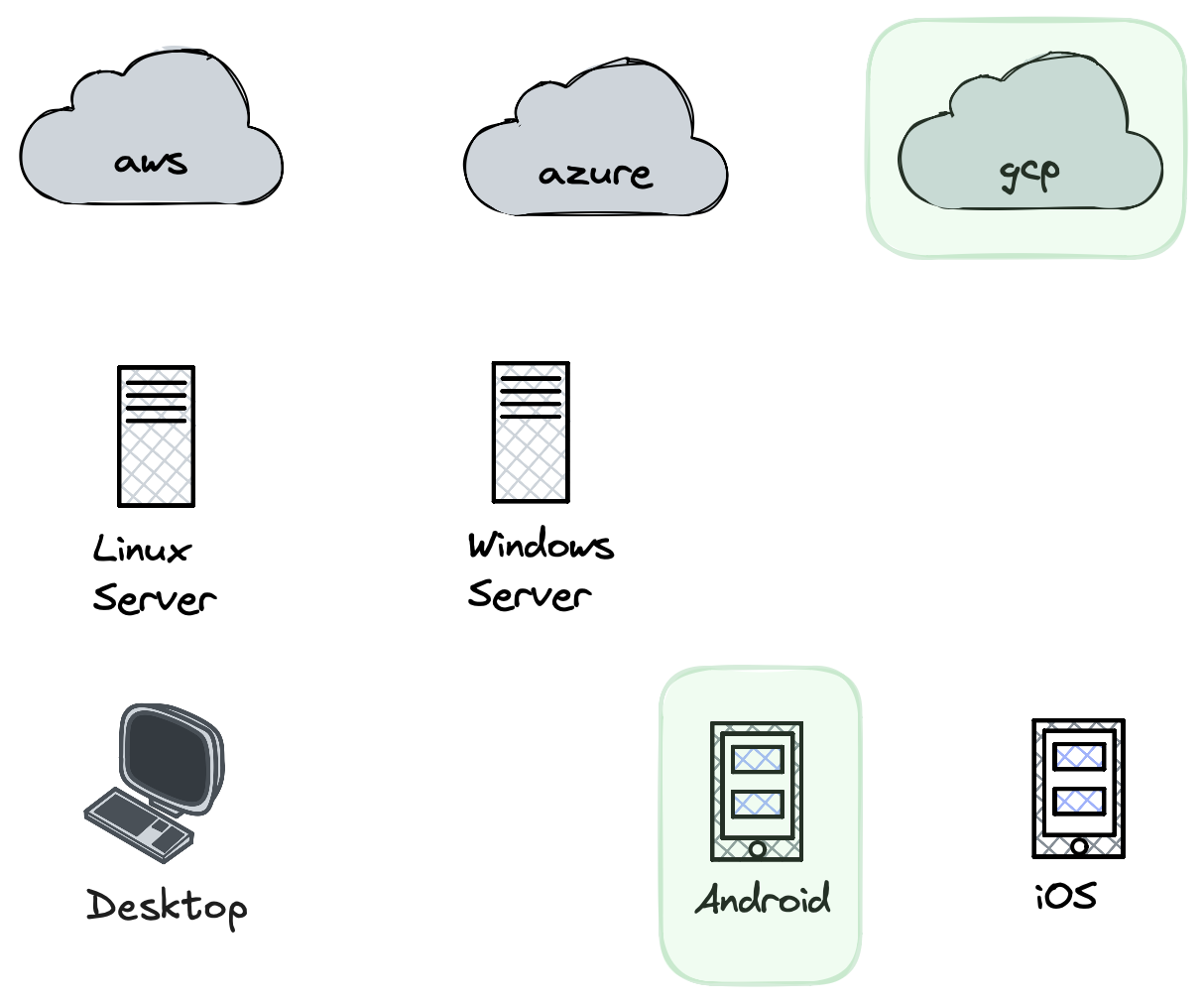

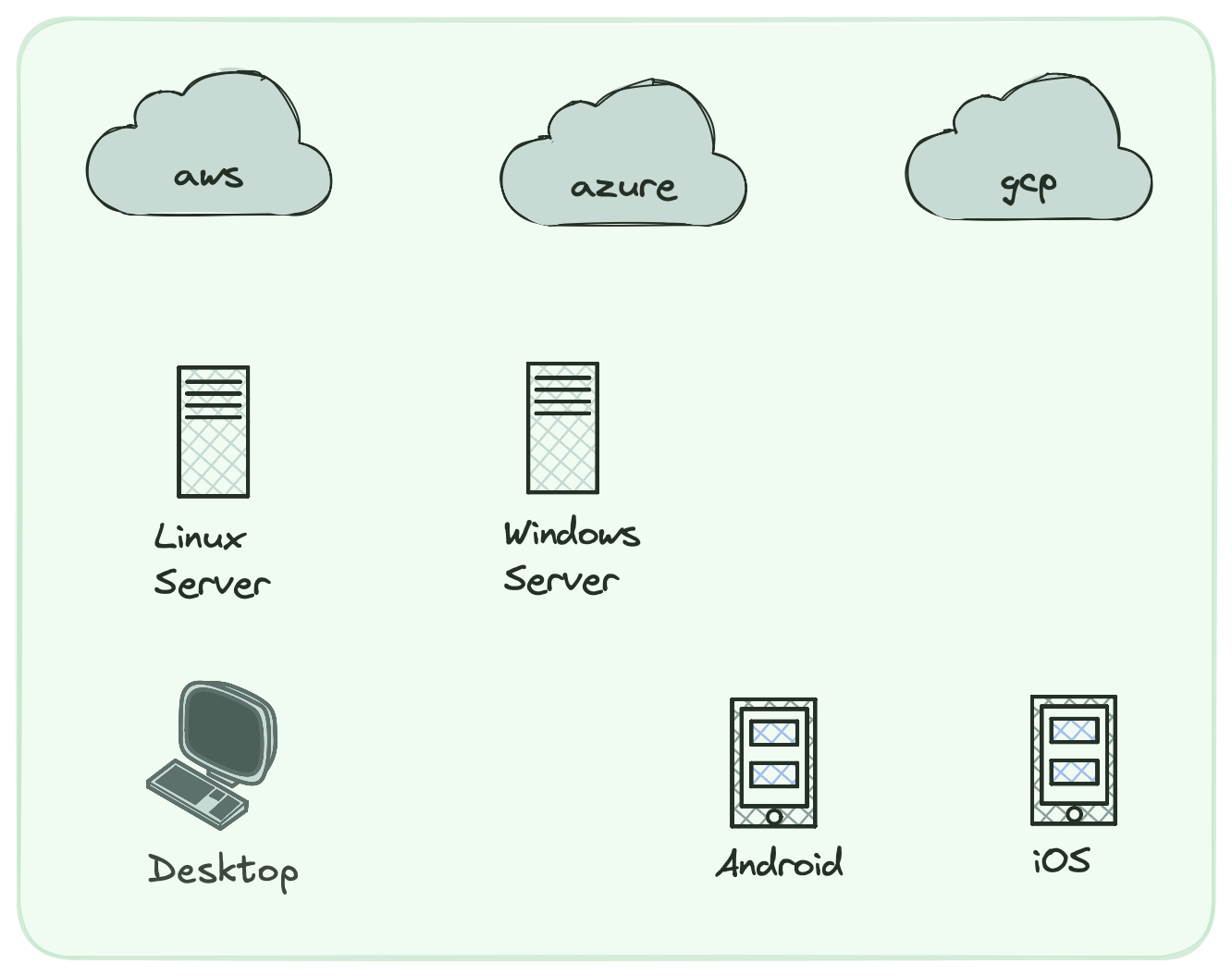

Take as an example Microsoft, with their Azure cloud they get visibility into some cloud services, but the true data mine for MSTIC is Microsoft Defender and Office365. They see little of the Android or iOS ecosystem, some of the server ecosystem, but a large chunk of end user data. In the case of AWS, almost the entirety of their visibility is into the AWS ecosystem and the same if we look at Apple who has their visibility on OS X and iOS endpoints almost exclusively.

Each threat research group only sees components of activity viewed through their lens.

These are different realms that have completely different actor profiles. Where Microsoft Defender may catch an end user infostealer malware running on a Windows 10 machine at a customer, AWS may then see that as C2 activity to a compromised EC2 node. Each threat research group only sees components of activity viewed through their lens. Each only gets a piece of the picture and their visibility into their respective platforms’ security tooling means they can connect wholly different instances than another group or may find no connection at all.

An Example

Apple may spot a new piece of malware being delivered via a WhatsApp exploit. They can see that being exploited, know which versions of WhatsApp are vulnerable, and have a vulnerability research team investigate. With the malware they have analyzed, they see similarities across 5 different binaries and they can link this to an actor they internally track.

Meanwhile, on Azure, Microsoft is only seeing data from iOS devices filling up block storage. They are aware that this is malicious activity because they know the Azure account being leveraged is compromised and they can tie this to a whole set of other malicious activity under an actor they internally track for having compromised a number of customer accounts.

Due to legal and contractual obligations, neither security team can share all of their security data with each other. If they can it’s wonderful and we see those collaborations where threat actors merge with joint reporting, but otherwise in their separate public reporting there will be a Microsoft actor that leverages compromised Azure accounts for exfiltration and an Apple actor that exploits WhatsApp bugs to steal user information. Two distinct clusters of activity on separate platforms viewed from different angles of visibility.

We see similar visibility problems with companies like Cisco or Palo Alto where the majority of their point of view is dominated by network device telemetry. They see network traffic, indicative of the behavior above, but they will not see the binary like Apple or the cluster of compromised accounts like Microsoft. They’ll see patterns of maliciousness between hosts that they may be able to identify as malicious through other reporting.

Expanding Visibility

Companies also aim to strategically improve their visibility through acquisitions as we have seen with Google acquiring Mandiant. Google’s prior threat intelligence group had good visibility into Android, Chrome, and GCP — a great spread of end user to cloud computing. Now with the acquisition of Mandiant they also receive the telemetry of Mandiant professional services performing on-site incident response. This greatly expands their collections to include AWS, Azure, and a whole host of endpoint devices when it intersects with a customer paying for MDR.

The Analytical Rigor Problem

A good analyst will never trust another company’s reporting at face value.

Now that we know that different actor names exist due to differences in visibility and scope, we can talk about why we don’t aim to combine them into singular groups. Threat intelligence analysts spend months if not years tracking actor activity, meticulously categorizing and cataloguing data to support their theories. When companies publish threat intelligence reporting they leave out the details, raw logs that prove how they reached their conclusions, and often times create parallel construction to not reveal sources and methods.

A good analyst will never trust another company’s reporting at face value and will take the time to parse the reporting and see if they can tie any of the indicators of compromise to activity that they have witnessed in their environment. Blind trust leads to the problem of several years back where every bit of reporting was attributing broad amounts of activity sets to Kimsuky due to a couple of common, shared indicators. Being too quick to tie two clusters together doesn’t help later analysis and in turn defenders who then have to wade through piles of TTPs and unrelated indicators. Tightly scoped clusters of activity improve decision making.

For example a company may report the IP address of a VPS that was used to host a dropper, but there is no instance of that IP address in the analyst’s environment. While it’s important to monitor for the appearance of that IP address in the future, it should not be immediately attributed to the similar cluster of activity that analyst is tracking even if there is overlap in other indicators. An analyst must work from their point of view, their visibility, and confirm that the activity aligns with their own.

The Advantageous Solution of Separate Names

Knowing the visibility behind a threat report immediately informs how you can use the information.

So companies have a valid reason to create their own naming conventions and analysts have a valid reason to not mix their visibility. What advantages do we get though from maintaining this Rosetta Stone of names? For that we have to come back to the visibility problem.

As we established, threat research groups have specific visibility and therefore capabilities and they also often hide their sources and methods in reporting. Knowing that a cluster of activity is under their threat actor naming convention gives an external analyst a starting point of where to look. Is this reporting on a ransomware group from Microsoft? You can assume you want to look for its activity in your Microsoft Windows fleet. Did AWS report on recent exploitation attempts it witnessed? Start by looking at your cloud resources for activity.

The point of a threat intelligence group is to inform and guide decision makers. For strategic intelligence, specificity matters. Incident response groups do not have time to waste chasing piles of indicators. Knowing the visibility behind a threat report immediately informs how you can use the information. More specific reporting, tightly scoped to company visibility is better than more generic, overloaded threat groups. Furthermore you can decide on a per company basis if you trust their reporting or have been able to confirm their reporting in your data in the past.

Threat naming conventions seem a jumbled mess across organizations, but they give us more visibility and insight than monolithic, overloaded actor groups. By thin slicing just what organizations can specifically see and verify, we can track and report on threat actors with increased specificity while building the amalgamations ourselves where proven.